The First Rule of Storytelling

In what may have been his best professional moment, fictional ad executive Don Draper said, “There is a rare occasion when the public can be engaged on a level beyond flash … in Greek, nostalgia literally means the pain from an old wound. It’s a twinge in your heart, far more powerful than memory alone.” See the full scene here.

“Flash” is synonymous with Super Bowl ads. Along with celebrity and novelty, it’s a mainstay of this blessed national day of consumption and violent team sports. (Could we even have a halftime show without flash?)

But StoryDriven is not just in the ad business; we’re in the story business. And the first commandment of story, according to director Andrew Stanton, is:

“Make me care.”

Flash makes you look, but it doesn’t make you care. The same goes for celebrity, novelty, and even humor.

Just because you laugh, doesn’t mean you care. Just because you recognize some beloved celebrities, doesn’t mean you’re emotionally invested in the content. Just because your expectations are subverted, leaving you to say “What in the love of all that is holy did I just watch?” doesn’t mean you form a bond with the brand. (For the record, I love all of these spots, even though none of them make me care about the story or product.)

The first commandment of storytelling:

Make me care.

-Andrew Stanton

Formulas to Sell

We live in a world of formulas. There are formulas for success, child rearing, job searching; the list goes on. And of course, there are formulas for Super Bowl commercials. Every commercial aired on Sunday followed a formula.

I’m guessing Audi’s spot was generated by a neural network fed an exclusive diet of millennial tweets (Maisie Williams + Let it Go + Allusions to Fighting Climate Change = … Good Advertising?)

But by far, this year’s worst case scenario following the celebrity/novelty/flashy formula is this spot by Proctor & Gamble, which is one of the most infuriating camels I’ve ever come across. But that’s another post.

Google’s spot Loretta follows a different formula from its contemporaries. It follows the formula for story.

For those of you who didn’t watch or whose memories couldn’t fully absorb the smorgasbord of spots, Loretta gives us an intimate view into an old man’s daily life. Early on, we can infer that he is a widower and that he adored his deceased wife. Through a dialogue with his Google assistant, we learn of their vacations to Alaska, their favorite movie, and what Loretta wanted for her husband after she passed (“don’t miss me too much, and get out of the dang house.”) Finally, we end on a bittersweet note – the sound of our unnamed hero leaving the house to take the dog for a walk.

If you haven’t yet, watch Loretta below and keep the tissues handy.

A Formula to Make Me Care

So what makes Loretta a successful 90-second story? Basic storytelling. There’s no flash, celebrity or novelty needed.

What is the formula for story? Hero, desire, and obstacles. (Stakes and tension keep us interested over longer periods of time, but that’s another post.)

Hero

Sometimes called the protagonist, our hero is the person, animal, or robot that the story is about. This is their story. The first rule for the hero is that the audience has to care about them. It helps if the audience sees a piece of themselves or a a loved one in the hero. In this ad, the hero is obvious – he’s the voice of the video. I personally care about him because he reminds me of my dad and grandfather. He has a kind voice, asks nice questions, and clearly feels love for his wife; all of this adds to his relatability.

Desire

The desire is what the hero wants. It should be straightforward, universal, and bring the audience closer to the hero. It can sometimes be more than one thing, but one desire should take precedence over the rest.

In Loretta, our hero’s desire is to remember his wife. Straightforward, universal, and relatable. He also wants to do right by her and live his best life, but in order to do that, he has to remember her, which takes precedence.

Obstacles

Obstacles often make or break a story in advertising. Many companies refuse to associate their brand with negativity, so they minimize obstacles or omit them completely. But without them, there’s no story.

“I went to the store to get milk. I got the milk and came home.” — Not a story!

“I went to the store to get milk. But when I got there, a bear had somehow made its way into the store and was wreaking havoc in the dairy section!” — That has all the makings of a story – and the obstacle makes up for a ho-hum desire. Don’t you want to know how that ended? Are you at least a teensier bit more interested to know whether or not I was able to get the milk?

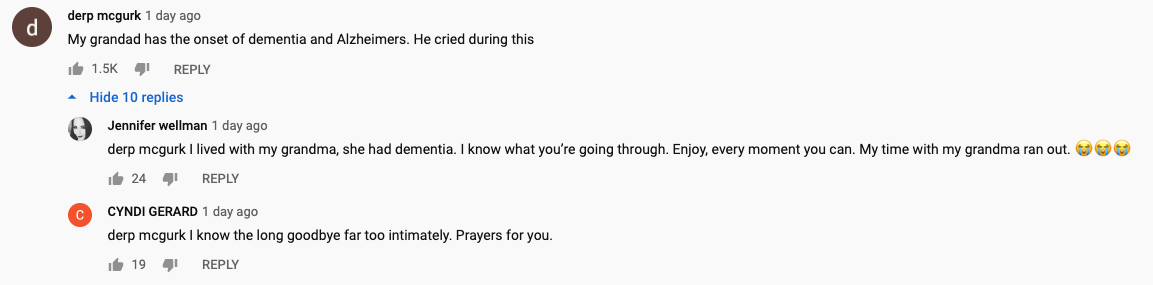

Like the desire, the obstacles are strengthened if they’re straightforward, universal, and bring us closer to the hero. In Loretta, the obstacle isn’t exactly spelled out, but if you pay attention, you see it: our hero is in the beginning stages of dementia. Talk about a difficult (but extremely relatable) obstacle.

Forming the Story Loop

Together, the hero, desire, and obstacles form a story loop, also called the binary question. Until that question is answered (Usually along the lines of “Will the hero achieve his desire?”) and the loop is closed, the audience cannot look away. If you’re interested in learning why, check out this post by Nathan, where he explores the Binary Question and how it keeps our attention.

A story is comprised of a hero with a desire, who faces a series of obstacles in order to achieve it.

Using Story To Sell

To dive a little deeper, what makes Loretta a successful brand story? After all, ads have a purpose, and those purposes relate to brands.

Be the Guide

Google set itself up to help our hero overcome his obstacles (at least temporarily) and achieve his desire. It really is that simple. At the end of the spot, thanks to Google, our hero remembers that Loretta wanted him to get out of the house, and we hear him take the dog out. They aren’t the center of the story, but without them, we wouldn’t have a happy ending.

Too depressing?

I’ve heard people say Loretta was too depressing for national television, for an event like the Super Bowl, and for advertising in general. (After all, the spot was preceded by a trailer for the new James Bond movie and followed by a saccharine ad for hummus.) What this argument assumes is that the range of emotions allowed in an event like the Super Bowl and on the national stage is limited. This argument assumes that ads should exclusively inspire us, make us laugh, and help us feel some escape from the crushing outside world.

I respectfully disagree.

It’s okay, even healthy, to explore emotions like grief, depression, and shame in a context like Super Bowl ads. I think it’s a sign of a society learning to deal with emotions and trauma in a more healthy way.

All in all, Loretta was out of place in the scrum of celebrity-driven, nonsensical, jokey, musical, bombastic ads – and that’s okay. In this context, it’s good to stand out because it gets you noticed. We notice this ad for the right reasons – not for flash, but for creating a twinge in our hearts, which is far more powerful.

We’d like to hear from you. Which spot(s) stood out to you, and for what reasons?

Big thanks to Reddit user rhodetolove for putting together this year’s spots in order.